Starting in October of 2018, I sent out the right front fender and hood sections to North County Powder Coating, to be gently and carefully sand blasted. This is the same firm that did such very nice work blasting & powder coating the Michigan’s frame. ( See my July 8, 2016) post “Blasted & Coated”) When these parts came back, the good news was that the parts were mostly solid and not laced with rust holes. The bad news was that there was lots of pitting on all the parts and the hood panels were both pitted and still warped (The hood panels were that way when we got the Michigan – not a result of over-zealous sand blasting or other problems we created.) In any case, the front right fender had been patched by Phillip Dickey (or the infamous Portage High students) probably sometime in the 1970’s. The left front fender (and the rear fenders) looked pretty good with little peeling or other defects. So….. now was the time to get these body parts primed and painted. But what sort of paint? In the course of researching “antique paints” it was apparent that “historically accurate” paints either don’t exist, are not clean air friendly (have high portions of volatile organic compounds – VOC) or would be prohibitively expensive to obtain. All of those point to simply using a modern paint system that will result in a durable finish not wholly inconsistent with the appearance one would expect on a car from 100 years ago. And…. how do we fill those awful pits in the metal?

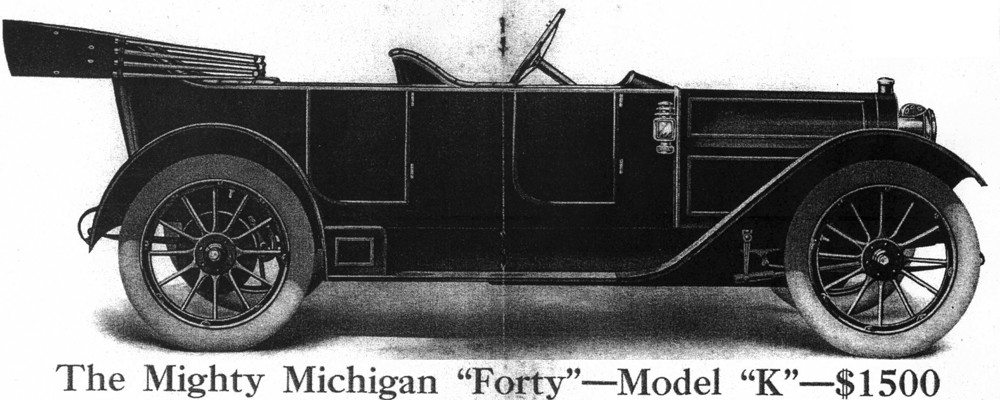

CHOOSING THE PAINT SYSTEM — One of the things that must be considered when restoring automobiles is what sort of paint to put on the car. These days the choices are numerous. They were NOT numerous when the Michigan was built in 1912, but that does not mean that the process was easy. Check out this description of the painting process that our car went through.

Click on image to enlarge – full brochure is in the PAINT post in the “NUTS & BOLTS” pull down menu.

MODERN PAINT TYPES: SINGLE STAGE or TWO STAGE? — The current automotive paint types are divided into two major types. We have single stage paints (pigment & sealer all in one) or 2 stage paints which have a base color coat with clear coat on top to make it shine. This has nothing to do with how the paint cures or dries. It DOES have to do with how many times you have to spray the finishing coats of paint. 2 stage paint systems require you spray at least 2 times. First with the base color coat and then second with the clear sealer. Single stage is theoretically sprayed only one time. Because this car is NOT a show car or museum piece, my instinct and knowledge as to what happens to paint on old cars that are actually driven pointed me in the direction of a SINGLE STAGE paint. I understand that touch-ups and color changes are easier if you DO NOT have to sand out a clear coat. So I’m electing to do an “all in one” paint job. Single stage is the system for me.

I am told that the paints come as lacquer, enamel, or urethane. Lacquer is old school and full of volatile organic compounds (VOCs) which contain solvents & such which are intended to rapidly evaporate into the air to dry the paint. These are becoming very difficult to find and are legally discouraged or actually illegal to spray in some states – such as California. This type of paint was used for MANY years and is some of what was originally used on the MICHIGAN back in 1912. Enamels and urethanes are the resins that the pigment (if any) is suspended in. I am told that these are sometimes mixed — making the distinctions between enamel and urethane truly confounding. The paint chemists would know — I would not. I am told that enamels are softer resins and dry to a glossy finish. Supposedly, urethanes of some sort are used by most new car manufacturers and are more durable than other paint types.

ONE PART vs. TWO PART / 1K vs. 2K — A one part (1K) paint is simply sprayed on and it drys by evaporation or heat or a combination. This is much like the old lacquer high VOC paints that relied on solvents evaporating in the air. A two part (2K) paint requires a hardener or catalyst to be added just before spraying and then reacts, hardens or dries chemically. It is similar to a very thin 2 part epoxy glue. If you don’t add enough hardener or catalyst, the glue or sprayed paint will never dry. Or if you add too much, the glue or sprayed paint will set up hard before you can get it on the broken part or sprayed out of the spray gun. Oh dear… either not enough hardener or too much hardener is a mess either way. Almost all aerosol rattle-can paints are one part paints. Recently they have started to produce 2 part aerosol can paints. They all require a system to break open a catalyst pack inside the can and each and every can will be very pricey. It would be nearly impossible to mistake one part and 2 part aerosol cans. Generally speaking, we understand that the chemical bond in a 2 part paint has a more durable finish than the 1 part paints. So it sounded like we probably wanted a 2 part paint on the car. O.K., so what are the downsides? All of these paints have components that evaporate or react to allow the paint to dry. None of this stuff is good to breathe. Indeed, commonly used solvents in 2 part (2K) catalyzed paints often contain isocyanates, which are poisonous. While all spray painting should be done with filter masks, the 2 part (2K) paints require a bit more protection — a lot more. Fresh air systems are recommended by the experts and they cover all exposed skin with Tyvek or similar zip up bunny suits. Exposure to these chemicals can cause permanent respiratory problems and strong allergic reactions. So……. I got the bunny suit and a fresh-air hood to do the painting on this car.

Filling the pits, dings and bumpy splices –The right front fender had two sections spliced in. Both repairs appear to have been brazed in by overlapping the pieces and NOT butt welded. That means there was additional thickness at the overlap from old to new steel. That means “a bump” where the steel overlaps. The only way to make this disappear is to hammer it as flat as you can ON THE EXPOSED SIDE without distorting the area and apply body filler to blend out the bump. I can tell you that this took hours of multiple applications of filler and block sanding until the result was basically invisible on the top side of the fender. Unless I decide later to get very picky – the splices will be visible UNDER the fender. It’s black under there, behind the wheel & tire and folks will be looking at other stuff. I’m not going to worry about it at this stage. If you want to crawl under the car and look at the back side of the fender – be my guest. No apologies. I want to get this car back on the road.

The actual painting and sanding had to wait a really long time. Because we were doing this outside (no mist & no breeze), and because Southern California was experiencing an unusually rainy Winter, our first perfect painting day wasn’t until March 23, 2019.

For reference purposes, I am using the following products:

Body Filler — SMART, Ultra Premium® from FinishMaster

High Solids Primer Paint — Restoration Shop® RP 2100 urethane primer with RH 4201 urethane hardener from TCP Global.

Sand paper — 80 grit 3M®, 120 grit 3M and various other 60, 80, 120, 220, 400 grit paper and lots of it. Dura-Block® sanding blocks for the flatter areas and Soft Sanders® sanding blocks for the weird bendy curves and raised bead areas. I have been experimenting with other materials that I can use to sand the raised beaded areas that were formed into the fenders and hood sections for stiffening. These raised sections were very common on early cars, especially so on large flat areas or where vibration was greatest – like front fenders. So far — I have not found a perfect solution for sanding those design features. The Soft Sanders, have worked “O.K.”. Adhesive backed sand paper is a must with these sorts of sanding blocks. The combination of soft sanding blocks and sticky-backed sandpaper works pretty well either sanding wet or dry.

Elbow Grease® by yours truly & my Dad. And lots of it.

DA (dual action) sanders work “o.k.” but frankly they aren’t very helpful on very flat surfaces or areas that have raised beads. It could also be rookie operator issues. But……. I am getting better.

As of the date of this posting (June 3, 2019) I’m ready to put on a finish coat of black on the fenders, splash aprons, and hood – but haven’t had a nice calm, sunny day yet. I also usually need a “hose tender” to keep the air hoses from getting tangled while I dance about in my bunny suit and try to stay focused on spraying. But we’ll get there.

I will also let you know how happy I am with these paint & other choices when I get further along in the process.

UPDATE: June 9, 2019 – I sprayed the fenders and splash aprons JET BLACK. They look really nice and shiny.